By Annette Espinoza

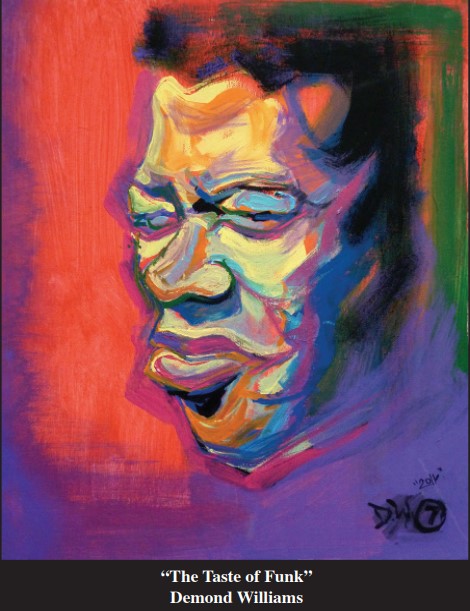

Our previous few editions have featured the vibrant and joyous work of Trenton native Demond Williams. Here is a look into the life of the man behind the brush.

“It all started with graffiti,” Williams recalls. From the age of 12 to 18, the thrill of his one and only vice was defacing the walls of his own city. But before that, Williams remembers spending hours drawing as a child. It was a drawing of Mickey Mouse that assured him and his parents of an opportunity, a “way out” of the plights of a troubled city limiting black men like him.

It was Williams artistic nature that paved a way for him: cultivating his skills to explore and express the world around him through color, even when it was at its grimmest. The artist’s signature method of mixing surrealism with visually jazzy and bombastic tones is meant to convey fluidity and movement in his work. This and his many other artistic choices are all deliberate and are meant to take his audience by surprise—they push beyond the boundaries of the ordinary.

But before he was able to press his tools against a canvas, his first strokes of colors were on cardboard and then the streets of Trenton. “I don’t know how to be bad, it’s just not in me, but graffiti was my bad.” Before enjoying the modesty and safety of being behind a canvas, Williams remembers a time where art was not as simple. Knowing that his parents would be disappointed and the high risks of being arrested and ticketed associated with being caught vandalizing, young Williams was always cautious. Nevertheless, it was an exhilarating feeling for him.

Williams outgrew the adrenaline of the graffiti after a piece was interrupted by the bouncing blue and red lights on the wall of a city street that he was working on. He remembers hiding against the floorboards that night. And although determined to finish his work, the lights were too daunting and he left the peice unfinished. “

It was time to take it to the next level so I began to work on painting cardboard boxes and then canvases,” said Williams. He also worked to fine-tune his artisitic abilities and pursued a bachelors degree in commercial art. With increased knowledge of terminology, technicalities, and guidelines as to what “good art” was, Williams felt boxed in; after the death of his father, the young artist took a sabbatical to make art his own way. His biggest take away from one particualrly challenging and unusal assignment. The assignment was to paint a brown paper bag with every color he saw on the bag with the exception of brown. Williams knew exactly what his professor meant. Understanding colors through values of hot and cold, the colors he saw went well beyond just the earthy brown; he recognized deep blues and hot reds and saw into the texture of what the bags looked like when it was crumpled.

“It was a language I understood. It was unorthodox and I could relate to it,” Williams said. Soon after this assignment, the artisit crossed paths with the Trenton Community A-TEAM (TCAT). There, he shared creative spaces with other aspiring artists including Walter Roberson and Susan Darley (among many others), who inspired and motivated one another.

Currently living in Georgia where he copes with Multiple Sclerosis, Williams looks back fondly at his time in Trenton, his youth, and his time with TCAT. Art to him is not just about the completed piece. In the process of creating his work, William’s can feel his heart racing and his head flooding with memories, emotions, and thoughts.

At times he expresses that these sensations can get overhwelming to the point where he is forced to walk away. And yet, to Williams, this is the beauty of art—in all its forms: “I love the moment when you see musicians hold a tune, that bliss, and satisfaction of holding and controlling this instrument that manipulates emotions and makes people feel sad or good. That’s what music and art does.”

While his style has certainly changed over the years, Williams will always return to his artisitic roots: on a recent trip to a gallery with his wife and children, he remembers seeing a piece called “White on White”. “All I could think of was how to deface it.”

Williams continues to make art and often sends it back to TCAT where his pieces hang on the wall of the soup kitchen (TASK) and TCAT’s newest building, Stockton 51. Other pieces are special orders and inquiries that he gets from his self-managed Instagram page where he showcases his work.

So what does the future hold for Demond Williams? “I want to have my work in galleries and have my work viewed by a wider audience. I have a lot to cultivate, I am still a student and I am defintiely still learning.”

You can find Demond’s work on his Instagram account (divinetreeurban) and reach him via email at divinetree7@gmail.com.